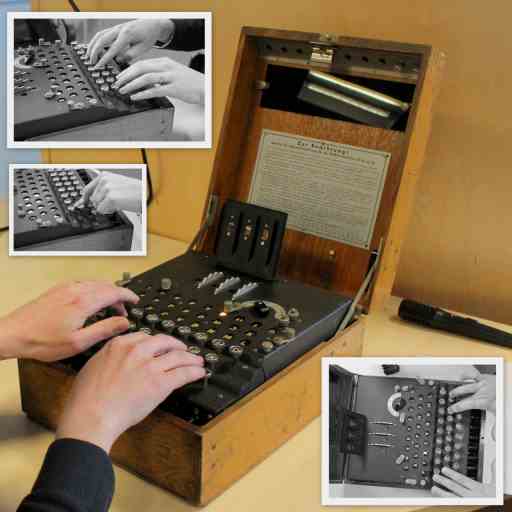

Data Collection

The Overview

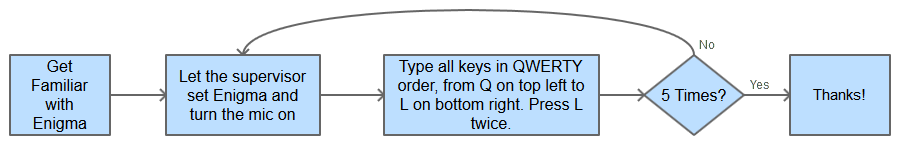

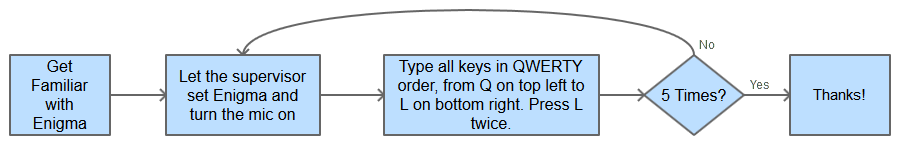

Each participant was asked to proceed as follows. The three rotors were to be set to the same initial positions, denoted as (1,1,1), and the participant had to type a sequence following the order in which they appeared on the keyboard - more specifically, starting with Q in the left hand top corner, through to L in the bottom right hand corner, and then repeating the letter L once more, hence 27 key strokes in total.

Other than the rotor settings, which had to be re-initialised to (1,1,1) after each set of 27 keystrokes, all other aspects of the Enigma's setting were left unchanged for the duration of the experiments.

The procedure, as it was conveyed to each participant, is given below.

During recording, a supervisor was responsible for controlling the recording, setting the rotor starting positions, and observing that the participant followed the procedure correctly, finally checking that the Enigma rotor positions had reaching the defined final setting.

The recordings were made in a conference room. We used an ordinary hand-held microphone, and held the microphone roughly 20 centimetres from the Enigma while recording.

We used the open source Audio Editor and Recorder Audacity to control the recording.

All recordings were set to the sample rate of 44100, 32 bit per sample in mono mode.

Given the conditions the final recordings contain occasional background noises as well as the keystroke noises.

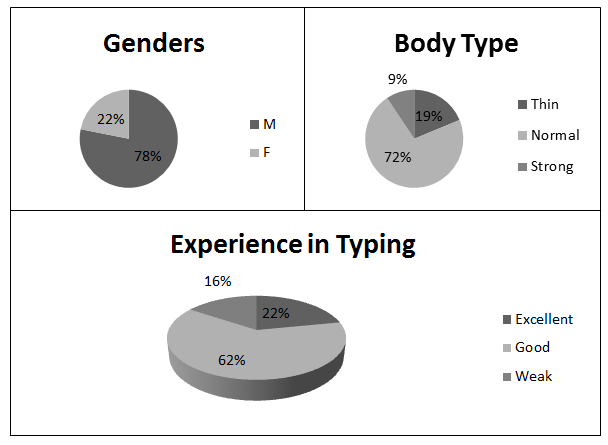

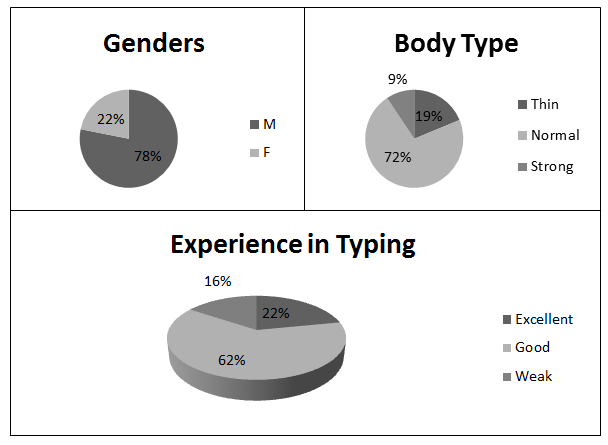

We recorded 32 participants in total. Their ages ranged from the 20s to the 70s. They were of different genders, body strengths, and typing skill levels.

The distribution of participants with regard to the ages, genders and experience in typing are shown in figure below.

Each participant typed the 27 letters five times in a row. We found that, since the Enigma keyboard is hard to press, the participants were usually quite tired after the third round or so, and from then on typed more slowly, thus helping to fulfil our third requirement.

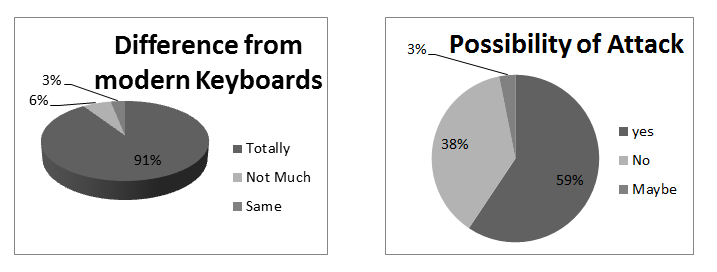

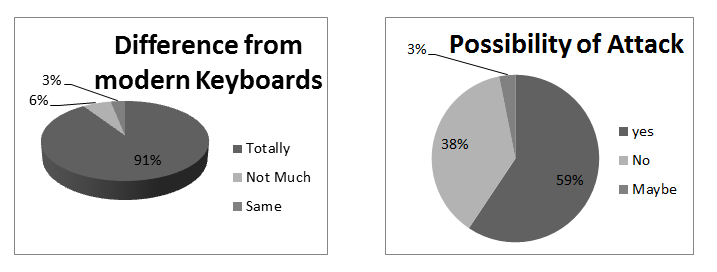

Most of the participants found the Enigma typing experience totally different compared to modern keyboards.

Each participant typed the 27 letters five times in a row. We found that, since the Enigma keyboard is hard to press, the participants were usually quite tired after the third round or so, and from then on typed more slowly, thus helping to fulfil our third requirement.

Most of the participants found the Enigma typing experience totally different compared to modern keyboards.

We asked the participants to type the final key "L" twice. This ensured that there was one double rotor movement.

In fact, the way in which the Enigma was set up, before the first pressing of "L", when the Enigma rotor sequence had reached (1,1,26), only the rightmost rotor had moved.

Then the next keystroke, i.e., first depression of the letter L, caused both the middle and the rightmost rotor to move, so leading to position (1,2,1).

On the second pressing of "L" only the rightmost rotor moved. Thus we captured the basic sounds of all the different keys, and one instance of a key-press that caused a double movement, from each typing sequence.

This enabled us to satisfy, at least minimally, the fifth expectation, and to assess the recognition of double rotor movements as well as all the different keys when they caused just a single movement.

Each participant filled in a debriefing form at the end of their recording session. They were asked two questions. The questions were as follows:

- How different was typing with Enigma comparing to the modern Keyboards? (Answers: Totally, Not Much, Same)

- Do you think that it is possible to identify the keys stroke just from the sounds produced by typing? (Answers: Yes, No, Maybe)

Participants' answers to the debriefing questions are illustrated in figure below.

As you can see, Nearly 40% of the participants rejected the possibility of performing Acoustic Side Channel Attack on the Enigma.

As you can see, Nearly 40% of the participants rejected the possibility of performing Acoustic Side Channel Attack on the Enigma.